That’s Lilly Sorghum, late twenties, Afro-Caribbean heritage, effortlessly put together, never without her dog. She’s sitting on a Brooklyn sidewalk holding an Erewhon smoothie like it’s the most natural thing in the world. The light is good. The composition is good. The dog is looking at the camera the way dogs do when they know they’re being photographed.

The image cost four cents to generate. Lilly doesn’t exist.

Last September, a woman named Eline van der Velden stood up at a conference in Zurich and announced that her AI-generated actress — a synthetic person called Tilly Norwood — was in talks with a talent agency. Emily Blunt and Whoopi Goldberg publicly condemned it. Van der Velden received death threats.

The backlash proved something worth paying attention to. Synthetic people are now consistent and believable enough to genuinely unsettle an industry. But Tilly was an actress — a controlled context, scripted roles, somebody else’s set. What about influencers, where the content is the product? Where the entire value proposition is a person holding a thing in a place with good light?

I wanted to find out how hard that is now. Not hard as in “can a well-funded studio do it.” Hard as in “can one person, alone, with no photography background and no design training, produce a portfolio of brand-partnership-quality images with a consistent fictional character.”

The answer took an afternoon and cost less than a coffee.

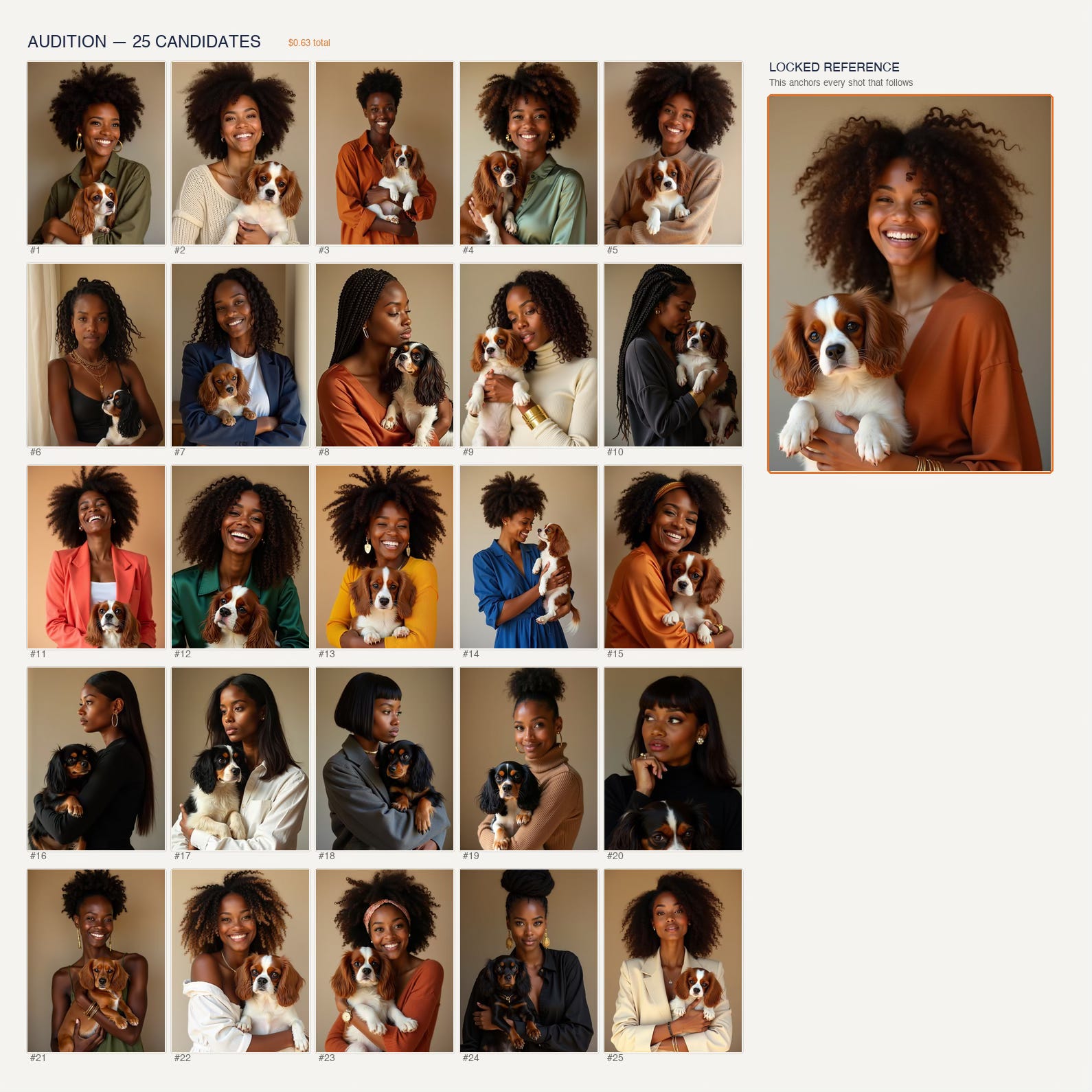

The Audition

You start the same way a casting director does. You generate candidates and you pick one.

Twenty-five faces on a grid. Like headshots pinned to a corkboard. I scrolled through them the way you’d flip through a stack of Polaroids — quickly, looking for the one that stops you. Number seventeen stopped me. Something in the expression. A steadiness.

That’s Lilly. From this point forward, every image I generate uses her face as the anchor. Her look, her dog, her vibe — locked. She doesn’t drift. She doesn’t age between shots. She’s as consistent as a real person, which is exactly the problem and exactly the point.

Total cost for the audition: sixty-three cents.

Why This Wasn’t Possible a Year Ago

I want to pause here because this part matters. Twelve months ago, keeping a synthetic character consistent across images was the hard problem. People would tell you to “train a LoRA” — a kind of custom model you’d build from reference photos. It sounds simple. It wasn’t. Hours of training, fiddly settings, and by image twenty the face would start to drift anyway. Her jawline would soften, her skin tone would shift, she’d age five years between the coffee shop and the airport. The AI videos you saw online were mostly that jump-cut Vox-style narration, not because creators liked that style, but because they couldn’t show the same character in two consecutive shots. And if they managed that, she’d be wearing different clothes. Forget about putting a real product in her hands.

You don’t have to worry about any of that now. Three things changed.

Character consistency is solved. A new generation of image models — the one I used is called Flux Kontext — takes a reference photo as an input. You hand it Lilly’s face once and say “this is her.” Every shot that follows preserves her features, her skin, her bone structure. No LoRA. No training. No drift. You pass the photo in, you get her back out.

Product insertion actually works. This is the part that surprised me. You give the model two reference images — Lilly with her dog, and a flat product photo. A photo of a Rimowa suitcase on a white background, say. Then you describe the scene: “airport terminal, golden hour, suitcase beside her.” The model doesn’t just paste the suitcase into the frame. It rotates it to the right angle, matches the lighting, adds reflections on the aluminum, scales it correctly against her body. It understands that a suitcase sits on the floor and a bottle sits on a table and headphones sit on a head. It gets the scene logic right — most of the time.

There are even models now that can dress a character from a photo of an outfit. Hand it a picture of a dress from a catalogue and a reference of your character, and it puts her in that dress like a digital Barbie. I didn’t use that here, but the point is: the building blocks exist to generate an entire influencer’s life — wardrobe changes, locations, products, moods — from nothing but reference photos and plain-language descriptions.

Four Brands, One Afternoon

I gave Lilly four brand partnerships. Not random ones — the kind of aspirational, lifestyle-adjacent brands that real micro-influencers build careers around:

Erewhon. The smoothie. Brooklyn sidewalk, dog beside her, golden hour. This is the easy shot — a person holding a cup is about as simple as product placement gets.

Rimowa. The aluminum suitcase. Airport terminal, natural light pouring through floor-to-ceiling windows. The suitcase sits beside her like it belongs there, like she’s between flights and someone happened to catch the moment.

Hennessy. Candlelit speakeasy, the bottle on the table, the dog curled in her lap. Warm tones, shallow depth of field. The kind of image that makes you feel like you walked into someone else’s evening. Is that cognac bottle a little too big? Honestly, I’m not sure — I’m not a cognac drinker. But the scene reads. That’s what matters at scroll speed.

Bang & Olufsen. Headphones on a beach. Montauk, golden hour, the ocean behind her. This was the hardest shot in the set — and that’s where things get interesting.

What the Misses Tell You

I didn’t generate four images. I generated a hundred and twenty.

Thirty shots per brand. Like a photographer burning through rolls of film, knowing most won’t make the cut. The difference is each frame cost four cents instead of four hundred dollars in studio time. The ratio matters because the AI doesn’t nail every shot. Not even close.

Here’s what I learned — and this is the part that matters if you’re someone who creates visual content of any kind, whether that’s for a brand, a blog, an Etsy shop, a real estate listing, or a book cover.

Objects that sit beside the subject work almost every time. The Rimowa suitcase landed in nineteen out of thirty attempts. Just put it next to her and the AI figures out scale, lighting, reflections.

Objects the subject holds are harder. The Erewhon smoothie worked in eleven of thirty. Hands are still treacherous territory — sometimes the cup floats, sometimes the grip looks wrong, sometimes there are too many fingers involved.

Objects the subject wears are nearly impossible. The Bang & Olufsen headphones — those sleek, over-ear headphones that needed to sit naturally on her head — worked in two out of thirty attempts. Two. The AI kept putting them around her neck like a stethoscope, or doubling them, or scaling them to the size of dinner plates.

But here’s the thing that matters: at four cents per shot, a 7% success rate still gives you what you need. You cast a wide net. Most of it comes back empty. But you only need one good catch per brand, and thirty attempts at a dollar-twenty is not a problem anyone needs to lose sleep over.

If you’ve ever watched someone pan for gold in a creek bed, it’s that. You don’t expect every scoop to shine. You expect volume to find the flake.

How You Do This Without Writing Code

This is the part people assume requires a computer science degree. It doesn’t. But I want to be honest about exactly what’s involved, because “no code required” shouldn’t mean “no effort required.”

I should tell you something before I go further. I write code for a living. I’ve been using Visual Studio Code since before it had AI in it. I build integrations and production tools for enterprise clients. I’m telling you this because I want you to understand what happened next: for this entire project, the coding didn’t matter. I wrote a brief in plain English and looked at pictures. The fact that I could have written the code myself makes it more significant, not less, that I didn’t need to.

I used a tool called Claude Code. It’s marketed at developers, and I am one, but the skills it actually requires are closer to project management than programming. The interface is a Terminal — a text window where you type and it types back. No buttons, no menus, no icons. Just a conversation, except the thing you’re talking to can build software while you talk. You can use it too.

I run it inside Visual Studio Code, which gives me one place to see everything — the brief, the images as they come in, the videos, and the code if I want to look at it. For this project, I didn’t.

Before I generated a single image, I wrote a brief. Claude Code uses a file called CLAUDE.md — think of it as standing instructions pinned to the wall of a production office. I described the project the way you’d describe it to a photographer you just hired:

Here’s the character. Here’s her look. Here’s the dog. Here are the four brands. Here are the reference photos for each product. Generate thirty shots per brand, judge them on these criteria, pick the best.

That brief is the whole trick. You’re not hoping the AI reads your mind. You’re handing it a creative brief with constraints, a process, and success criteria — the same way you’d hand a brief to any creative professional.

Now here’s the part that might surprise you. I told Claude Code I wanted to generate images using an AI image service. I didn’t tell it which service to use. I didn’t tell it which specific model to pick. I didn’t hand it a technical manual. Claude Code already knows about services like fal.ai — it knows which models handle character consistency, which ones handle product insertion, which ones are good at what. It suggested the pipeline. It found the reference photos for each product online. It figured out how to pass Lilly’s face and each product photo into the model together. It wrote whatever code it needed to make all of that work.

I never looked at that code. Not once. I never read the documentation for the image service. I never debugged anything. I described what I wanted, set the constraints, and looked at pictures.

And those hundred and twenty pictures? They didn’t spool out of the machine one at a time like faxes from 1994. Claude Code ran them in parallel — all thirty shots for all four brands, generating simultaneously across the wire. Nine minutes, wall clock time, for a hundred and twenty images. I went to make coffee and it was done before the water boiled.

The entire technical skill involved is this: the ability to describe what you want clearly enough that a system can go execute it. If you can write a creative brief — if you can tell a photographer “I want her on a Brooklyn sidewalk at golden hour holding a smoothie with the dog beside her” — you can do this. The AI handles the how. You handle the what and the why. And if you don’t even know what tools exist to do the job, Claude Code will suggest them. You bring the vision. It brings the infrastructure.

The Part That Should Make You Sit Up

After I generated all hundred and twenty images, I picked the winners by hand. Best composition, best product visibility, most natural feel — the four you’ve been looking at throughout this piece.

Then I had AI evaluate every single image on its own, scoring them on eight criteria: character consistency, product visibility, composition, lighting, something I called “scroll-stop factor.”

The AI picked the same four winners I did. Not three out of four. Four out of four. Perfect agreement.

They disagreed on runner-ups, which makes sense — the best is obvious, the second-best is subjective. But the implication is hard to ignore: the entire pipeline, from creative brief to finished image to winner selection, could run without anyone watching. You could set it loose before breakfast and come back to a week’s worth of Instagram content by lunch.

The Cost, Plainly

The whole project — auditions, product prep, all hundred and twenty shots — came to $4.80. Nine minutes of actual generation time.

I’ll say that again because the number is worth sitting with. Five dollars and fifty-one cents. A hundred and twenty images. Nine minutes. One fictional influencer with four brand partnerships and a very photogenic dog.

A real photoshoot with a real influencer, real photographer, real stylist, real location — you’re looking at $10,000 to $15,000 for a single brand. Maybe more in New York. I produced four brand campaigns for the price of a gas station sandwich.

They Move Now, Too

One more thing. Those four winning still images? I fed them through a video model. Four seconds each, just enough for a social media clip.

The Erewhon — she shifts on the sidewalk, the dog’s ears perk up, the smoothie catches the light.

The Rimowa — she reaches for the suitcase handle, airport light catching the aluminum.

The Hennessy — candlelight flickers, she lifts her glass, the dog stretches in her lap.

The B&O — an ocean breeze moves the cardigan, the dog turns to camera like he heard something.

$1.96 for all four. The influencer breathes now.

So What Do You Do With This

Here’s where I’m supposed to either panic or sell you something. I’m going to do neither.

What I built was an influencer pipeline, but the bones of this process — write a clear brief, set constraints, generate at volume, let AI judge the results — those bones fit anywhere you need visual content with a consistent look.

You run a small business and need product photography with a human touch, but not a human budget. You’re a real estate agent who wants lifestyle shots staged in empty houses. You write children’s books and need a character who looks the same on every page. You’re building a brand from scratch and need six months of social content before you’ve made a dollar.

None of this required me to write code. I described a system in plain language — what I wanted, what the constraints were, what good results look like. Claude Code suggested the tools, figured out the technical pipeline, found the product references, ran everything in parallel, and even helped judge the results. The only thing I did was write the brief and pick the winners. And as we established, even the picking could be automated.

The difference between this and typing a prompt into an image generator is the difference between tossing seeds on the ground and planting a row with string and stakes and spacing. Both involve seeds. Only one of them reliably feeds you.

If you want the technical breakdown — the pipeline architecture, cost tables, and failure mode analysis — I covered all of that in the developer write-up of this same project.

The technology is here. It works. And it’s not slowing down. What you do with it is the only question that matters now.

Try This Yourself

You don’t need to build a four-brand influencer pipeline on day one. Start with one character and one product. Here’s how:

Get set up. Download the AI Starter Kit. It walks you through installing everything in about 20 minutes.

-

Pick a character. Open Claude Code and tell it: “Generate 25 headshots of a fictional person. [Describe the look you want.]” Pick your favorite. That’s your anchor.

-

Pick a product. Anything. A coffee mug, a pair of shoes, something you sell. Find a clean photo of it on a white background.

-

Write a brief. In your CLAUDE.md file, describe one scene: your character, your product, a location, a mood. Be specific — “Brooklyn sidewalk, golden hour, dog beside her” is better than “nice outdoor photo.”

-

Generate 10 shots. Tell Claude Code to generate 10 variations. At roughly $0.04 each, you’re spending forty cents. Pick the best one.

You just made your first piece of AI-generated brand content. Total cost: under a dollar. Time: about 15 minutes after setup.

Now do it again with a different scene. Then a different product. That’s how Lilly got four brand deals in an afternoon.